On Mattering and Mystifying Hair

Adrienne Edwards

I. Muses of the Ornamental

Hair braiding throughout Africa was historically a signifying system, in which ethnic groups, geographical origins, age, religion, social position, and marital status could be visibly ascertained merely by the elaborate patterns employed. Embedded in each motif was not only the story of a life but also that of a collective, which is to say a people. For the numerous styles of braiding are indeed embodied cartographies of long gone and newly fresh encounters, proving authenticity a fallacy, and referenced highly metaphoric symbols drawn from cultural objects (such as baskets, sculptures, textile designs), architecture, corporeal postures, body limbs, stylistically almost hieroglyphic.[1]

While often interpreted in the West as “natural” (in the sense of being unaffected), hair braids are highly cultivated aesthetic ornaments, often requiring or including, in addition to one’s hair, thread to extend the length of hair, combs, a long needle, perfume, and pomade.[2] Like other ornamental matter, hair braiding reflects and embodies circuits of exchange among diverse people; however, what it less understood about the process of becoming ornament is the fact that it is a demonstration of power. The ornament is an accumulation of refractions from myriad cultures, and these “borrowings” are possible because of encounters that have occurred as a result of demonstrations of social and cultural power. Indeed the ornament “an originally natural form undergoes such ornamental development as to lose its objective resemblance, it is an indication either that the original significance and symbolism have been lost or that the form is a foreign one which has been borrowed in fashionable emulation by a people for whom it has no significance or existence other than as a purely ornamental motive”.[3]

***

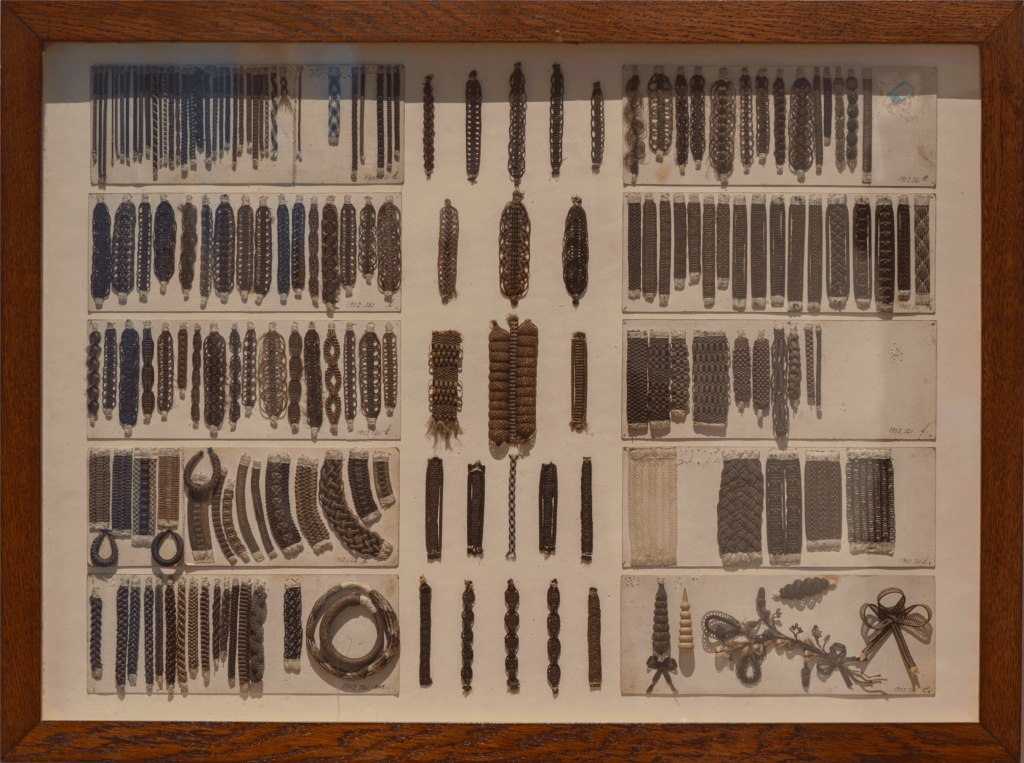

(August 2018; Puglia, Italy) While on vacation with my good friend and Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu and her family, as well as our friends, we spent our days visiting the “intimate” (as in small) sandy or limestone-pocked beaches, and our nights exploring medieval villages (with surprisingly distinct North African flairs) in search of local eccentricities and delicacies. Often on the beach we encountered West African women (namely from Senegal) carrying small portable taxonomies of hair braiding styles they proffered to us sun worshippers. Their advertisements are structured in grids, composed of an assemblage of images akin to J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere’s photograph Abebe. Similarly, reminiscent of Dutch wax fabric in the ways in which it appropriates socio-cultural and political symbols, produces the polyester cloth in Indonesia (formerly a Dutch colony), and sets bales of material out into the markets of sub-Saharan Africa and beyond, the Commes des Garcons shirt featured in Mobile Worlds makes the hair advertising board an icon. In so doing, the button down casual pink shirt amplifies the commodification of the migrant women’s very tool of commodification: the advertising board and renders it into high end designer wear, selling for far more than any of the services women who actually use such forms of marketing to sustain themselves could possibly hope to make in the time of a fashion season or eBay transaction in which it is sold.

There can be no doubt that African descent women – whether on the beaches of southern Europe or Caribbean islands or the streets of Harlem, East London, or Salvador de Bahia – commodify not only their skills (as they must) but also any cultural significance hair braiding has (its signifying capacity) shifts radically. The braids are now a compounded ornament: decoration literally employed as an expression of what one is willing to (required to?) sacrifice precisely by making its signifiers applicable to all and meaningful to none. And they do so in fluid spaces: The West’s international ports of rest amongst palm trees and bougainvillea. One morning, Wangechi, with her silver streaked braids, and I, with my mane bushy curls, alone (as our Italian friends were parking the cars) went ahead to secure the beach bungalows and chairs we had reserved for the day. My Italian is no longer fluent, but it isn’t incomprehensible either. We were directed to leave the beach, too intense a proximity, too closely resembling the migrant women and their wares. Mami Watas washed up from the sea.[4] The audacity.

***

Artist Sarah Amah Dua’s work employs artificial hair in hues of silver, blonde, red, black, and blue as material for her uncanny collection of dresses. Such bundles of weave are typically used to fashion and bolster braids or extend the length of hair needed to achieve a Rapunzel affect. Her wonderfully bizarre garbe is inspired by the striking difference between her hair, a curly Afro, and that of her peers; she has remarked: “My hair enters the room even before I get it…”. In ideologically structuring her work in relation to long-standing motifs of black women and our hair, Dua’s art is reminiscent of similarly themed works such as Lorna Simpson’s numerous conceptual photographs of hair and wigs with text, Danny Tisdale’s wall installation of hair extensions, Adrian Piper’s collection of jarred hair clippings, and Sonia Boyce’s collage series on black hairstyles, to name a few. Dua’s emphasis on the material’s artifice and her absurd move of using hair weave for attire follows and extends from the very history, prevalence, and importance of artificiality in the design of black coiffeur. Whether it is synthetic or culled from women in Global South countries like Brazil or India, which are among the most prized and expensive sources for human hair extensions, Dua reminds us that like hair braiding itself, the hair weave is an invariably different same commodity following the flows of capital, constituting new and equally complicated constellations of relation, ornamenting and being made an ornamental by women around the world. As art historian Kobena Mercer has written, “hair remains charged with symbolic currency”.[5]

II. The Virtues of Circulation and Accumulation

There’s an illuminating account of the history of a Hamburg-based, multi-generational family business that manufactured rubber combs through the very mysticism of capital, its shape-shifting ways and tendencies revealed. As the story goes, the family acquired the first license from an American company to make “artificial whalebone from hard india-rubber” in 1852, and the following year they manufactured hard rubber combs. The initial attempt failed, and after the development of tin molds and a water curing technique, the India-Rubber Comb Co. was founded in New York. The newly revised process was transferred to a special factory in Hamburg, indeed it was the first German hard rubber works establishment under the banner Harburg India-Rubber Comb Co.

As the company grew and was consolidated into a single family’s control, it also aimed to better command the source of its wealth, sending a staff member to Singapore to influence the mode of collection for the raw rubber. With the forests in Malaysia compromised from over extraction of the natural material, another envoy was sent to West Africa to establish a new factory. An important aspect of the discovery period, like so much of the European approach to the rest of the world, involved the cataloguing of the diversity of new material, replete with descriptions and samples, presented in structured displays not too unlike the late nineteenth century German Hair Chart. To control costs and armed with the knowledge of the natural materials, as manufacturing processes became mechanized, natural rubber was often combined with fillers. The goal was not only to maximize the natural material, but also to guarantee its quality and to exhaust its seemingly infinite possibilities by turning ebonite-vulcanite into other commodities, including black jewelry, pipe mouthpieces, fountainpens, ornaments, statues, facilitators for electricity, propeller shafts of ships, and so on.

– “The History of a Large Rubber Firm,” published in The India-Rubber Journal, April 1, 1906

III. The Mysticism of Desire

François de Salignac de La Mothe-Fénelon’s novel Les aventures de Télémaque, first published in 1699 and pivotal for the social and cultural history of France, exemplifies the ways in which classicism has been given the ornamental treatment.[6] Such appropriations are typically described as the social utilization of myths, a conviction that these legends can uniquely interpolate moral, social, and aesthetic concerns. Fénelon’s Eucharis is a “modern” invention of an ancient myth as the character is not actually featured in Greek mythology. Rather she, in the context of Les aventures de Télémaque, is an elaboration to Homer’s “The Odyssey”. At the center of a tale about personal struggle between passion and reason, resulting from a conflict between responsibility and love, as well as the risks of abandoning oneself to amorous dalliances, is Telemachus, the son of the Odyssey’s main character, Ulysses, and his unrequited love for Eucharis.[7]

Stories of captivated lovers and goddesses and nymphs reveling amidst vanity and luxury while bereft on island retreats taken in between conquests and adventures was a common narrative arch in classic literature. In this instance, Telemachus must leave the island of Calypso to assume his responsibilities despite the fact that he is enthralled with Eucharis. As the story goes,

He knows he must leave, but he uses his impressive powers of reasoning to justify at least a final meeting with her. Mentor wisely recommends a more decisive break and takes matters in hand. When he sees a passing ship, he pushes Telemachus off a cliff into the sea and then jumps in after him. They are rescued by the crew and continue their adventures until just before Telemachus is to be reunited, as in the Odyssey, with his father. At the conclusion, Mentor leaves the boy’s side, having revealed his/her true identity as the goddess Wisdom, guiding him all along. At the end of his journey, Telemachus is now capable of seeing beyond the immediate.[8]

What made Eucharis compelling for Telemachus was paradoxically the fact of her ordinariness, described as modest beauty[9], and what made this story compelling and meaningful in influencing the French state was its concern for moral progress and realization of potential, achievable through the disavowal of passions and illusions.[10]

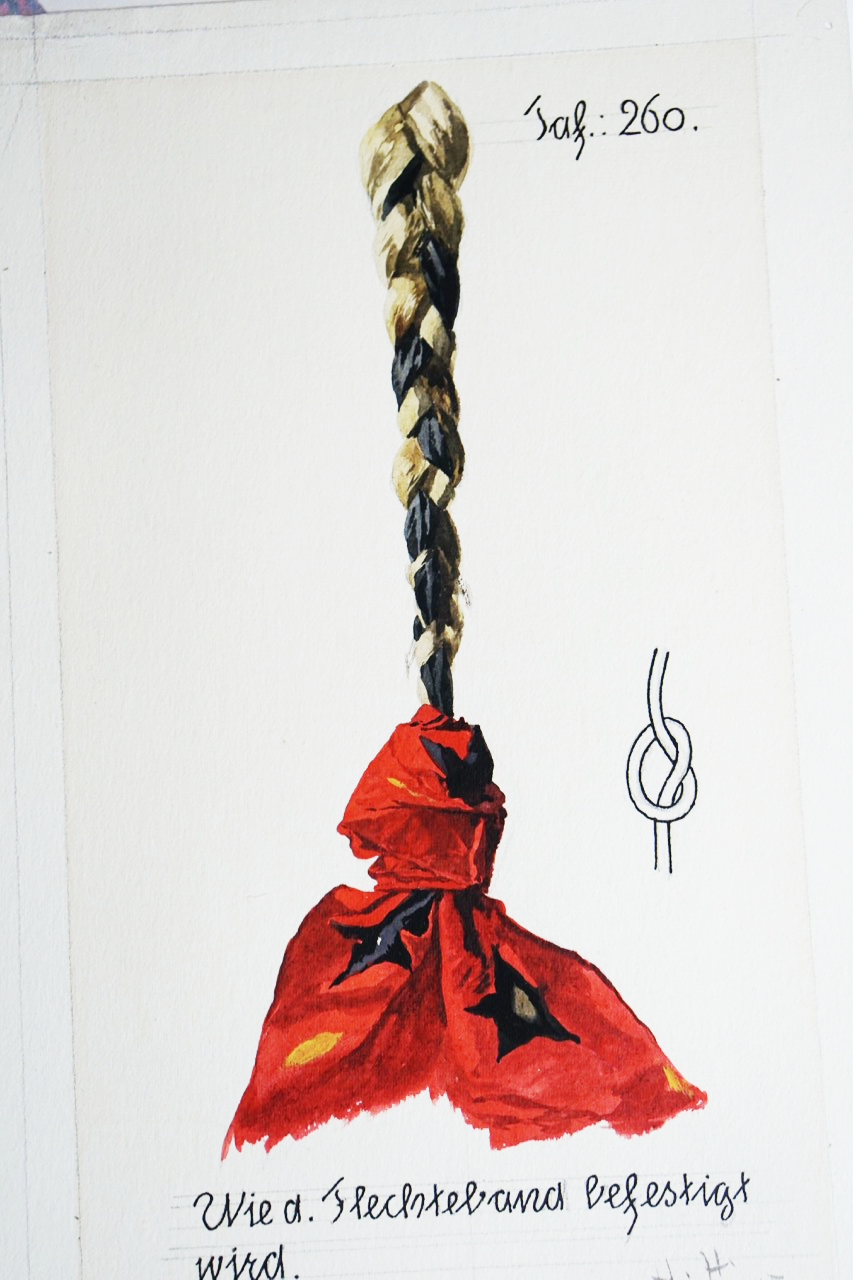

An adherence to the virtues of renunciation and sacrifice came to define the Victorian era in a particularly feminized way. A mode and means through which restraint and loss was commonly expressed and experimented with was through hair ornaments. They were a distinctly bourgeoisie Victorian fashion and hobby in which cut hair was cultivated into medallions, bags, ornaments, bookmarks, riding whips, pencil cases, perfume bottles, and jewelry; it was as much a popular past time of upper class women as knitting and crocheting. These bizarre objects often involved the creation of mourning fetishes composed of the locks of deceased children, family members, and lovers, as well as religious icons placed in quotidian spaces and daily attire. Though popular in the United Kingdom and France, such relics as the early nineteenth century horse hair embroidered Eucharis were importations from Germany.[11] Mourning medallions featured elaborately modified locks of hair mounted in a frame; the hair was often cut very fine, almost like a powder, and delicately applied to an image with glue.[12] The medallions also used tools similar to those employed in hair braiding: a thread, bobbins, knitting needles, and molds.[13]

Hair, as creative material, signified the Victorian obsession with nature as both sentimental and intimate, and also as an expression and concern for the inevitable: death. Godey’s Lady’s Book suggested, “Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials and survives us, like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or a friend, we may almost look up to heaven and compare notes with angelic nature – may almost say: I have a piece of thee here, not unworthy of thy being now”.[14]

For Walter Benjamin dying is “the moment when life becomes narrative, when the meaning of life is completed and illuminated in its ending”.[15] If the power of mythology is to be found in its unique capacity to give meaning to the ordinary, the powerless, to confront as a counterpoint to History, the relic, the material of death and its artifacts, is ubiquitous in the Victorian period for precisely the same reason.[16] Historian Deborah Lutz suggests that narrative qualities adhere to and animate the relic as “last words, but they also served as frames or fragments of the moment of loss”.[17] What remains is more than a lingering desire for the impermanence of death but also the possibility of existence elsewhere and as otherwise. There also remains the aura of melancholia in the Freudian sense as that which endures as a feeling of longing for longer than is reasonable, which instigates narratives based on individual lives and the ability of those lives to convey a broader meaning, to speak to something beyond the individual. Accordingly, for Victorians, “artifacts of beloved bodies still held some of the sublime, festishistic magic…”.[18] There is an undeniable erotics to hair elegies; the attendant performance of crafting the object for the purpose of a ritual, for the purpose of pining over a materialized individual now nothingness impossible to universalize. A dead commodity, an ornament.

[1] See Titus A. Ogunwale, “Traditional Hairdressing in Nigeria,” in African Arts, Vol. 5, No. 3 (Spring 1972), 44-45.

[2] Ibid.

[3] William M. Ivins, Jr., “The Philosophy of the Ornament” in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 28, No. 5, May 1933, 94.

[4] See Adrienne Edwards, Nguva na Nyoka (London: Victoria Miro Gallery, 2014).

[5] Kobena Mercer, “Black Hair/Style Politics,” in new formations, Number 3, Winter 1987, 36.

[6] Mary Vidal, “David’s Telemachus and Eucharis: Reflections on Love, Learning, and History,” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, No. 4 (December 2000), 706.

[7] Ibid., 705.

[8] Ibid., 707.

[9] Ibid., 704.

[10] Ibid., 708.

[11] Virginia L. Rahm, “Minnesota Historical Society Collections: Human Hair Ornaments”, in Minnesota History, Vol. 44, No. 2 (summer 1974), 71.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Deborah Lutz, “The Dead Still Among Us: Victorian Secular Relics, Hair Jewelry, and Death Culture”, in Victorian Literature and Culture, in Vol. 39, No. 1 (2011), 127.

[16] Ibid., 128.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.